Teens get a moving lesson on privilege, bias and stepping up

PROVIDENCE – The energy was palpable as a group of high school students crowded around tables on Jan. 22, talking excitedly over slices of pizza. Their dinner guests were a Rhode Island Supreme Court justice, a former R.I. lieutenant governor and a magistrate, all members of the state Supreme Court’s Committee on Racial and Ethnic Fairness in the Courts, and attorneys from the Rhode Island Bar Association’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee.

The speakers were welcomed to the Sandra Bornstein Holocaust Education Center’s LIFT program for the first of two sessions focusing on justice, civic responsibility and the importance of being an upstander.

The Leadership Institute for Teens, or LIFT, is designed to bring together students in grades 9-12, from different backgrounds, for seven months to learn lessons from the Holocaust and other genocides, practice leadership skills and participate in community service. In other segments of the program, the group has heard from such notable guests as Ada Winsten, a local Holocaust survivor; Kannyka Pouk, the child of survivors of the Cambodian genocide; and Tina Cane, poet laureate of Rhode Island.

The session with the judges and lawyers connected ideas about fairness, privilege and standing up for what you believe in.

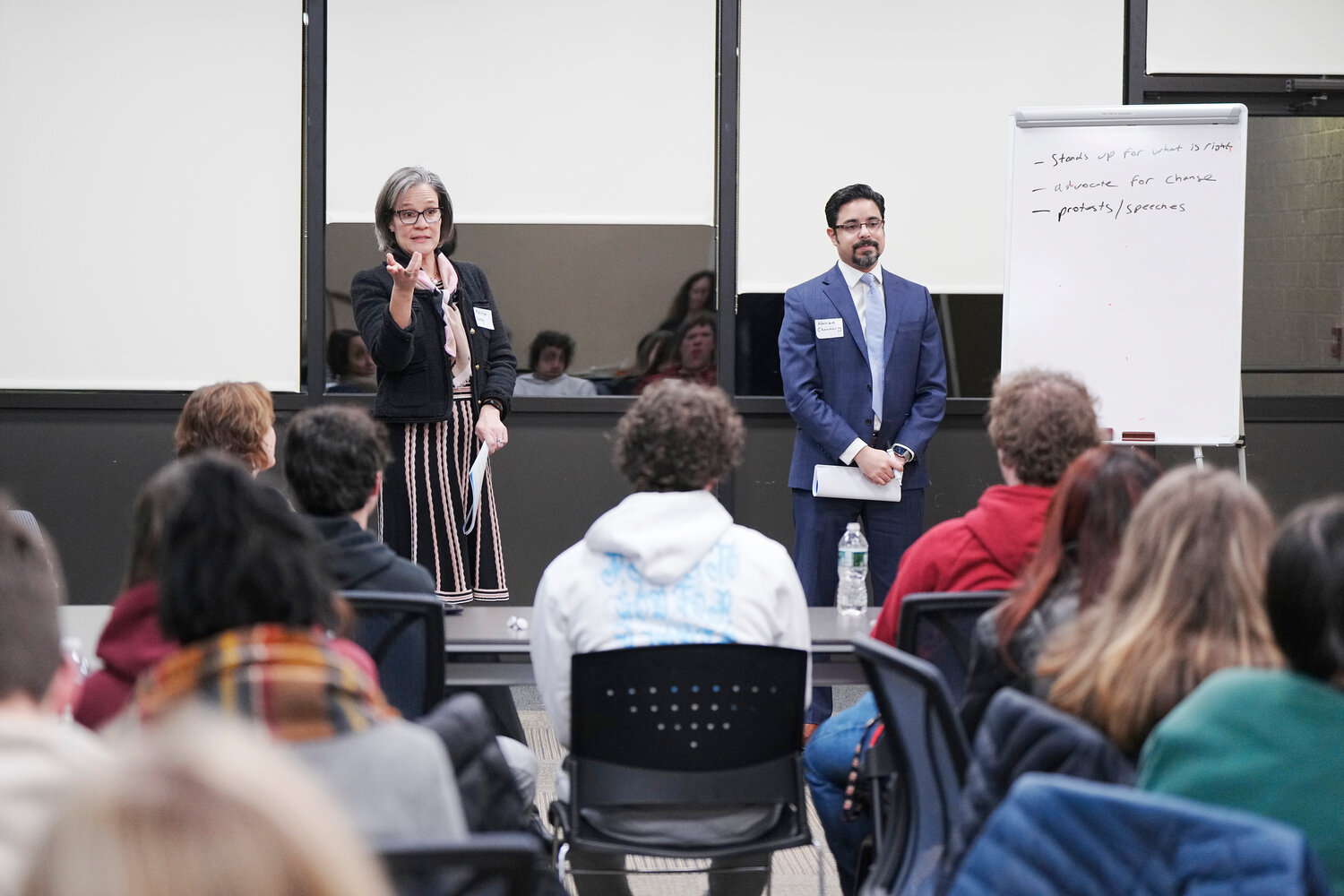

After the introductions, Supreme Court Justice Melissa Long led the teens in a brainstorming exercise about what it means to be an upstander. An upstander takes action to help, as opposed to being a bystander.

One student talked about his father as his hero, a strong person who protected him when he couldn’t protect himself. Another, who had just returned from Washington, D.C., said that she and a group of fellow students lobbied Congress to push lawmakers toward further action on climate change.

Magistrate Edward Newman told how he works with formerly incarcerated people to clear their records, which create a barrier to good jobs and places to live long after they have paid their debt to society.

The students also took part in an activity called “The Privilege Walk,” led by former R.I. Lt. Gov. Richard Licht. The premise is simple: everyone starts out in a straight line and, as statements about personal identity are read aloud, participants must step forward or backward based on their life experiences.

Example statements included, “If you have never had to worry about where your next meal will come from, step forward,” and, “If you are afraid to walk alone at night, step back.”

By the end of the activity, the participants had moved off the straight line, reflecting each person’s advantages and disadvantages in society.

A fascinating conversation followed. Attorney Bob Oster had come with his daughter, Sarah. As a parent and child who are both lawyers, they shared many of the same experiences, but Bob was at the front of the room and Sarah was several steps behind him at the end of the walk. Bob reflected on how sad it made him to fall out of step with someone he has tried so hard to nurture and protect.

Those in the middle were mostly White girls, who possessed privileges around race and economic status, but still faced sexism and threats of violence.

Two students of color, who attend the same school and grew up in the same neighborhood, did not end up next to each other. One of the students commented on how strange it was to find significant differences between them. Before the Privilege Walk, they had assumed the other person lived a life identical to their own. The revelation that they did not helped fulfill the purpose of the walk: to have the teens reckon with their own place in the world, but also to challenge their assumptions about others.

Ultimately, the lesson was that no one is totally privileged or not privileged; all people face challenges as well as advantages. But by recognizing how privilege, or the lack of it, affects an individual’s life, we can work to change the forces that enable it on a societal level.

The judges and lawyers stated that one important avenue to pursue justice is through the legal system and the government.

Judge Long described reading an article lamenting the lack of diversity in the judicial system and how, as a Black woman, she felt she had an obligation to step up. She knew her presence could play an important role in excising racial bias from the bench. She said she put her name up for consideration because she knew it was the right thing to do. In other words, she became an upstander.

The Holocaust center is hopeful that the LIFT teens will be inspired to do the same!

LIFT is partially funded by the Jordan Tannenbaum and Harold Winsten Family Foundation.

GIOVANNA WISEMAN is director of programs and community outreach at the Sandra Bornstein Holocaust Education Center, in Providence.